Greece’s Role in Europe–Africa Connectivity

Greece plays a pivotal role in the evolving energy and infrastructure corridor between Africa and Europe. Its strategic location at the crossroads of key maritime routes, combined with substantial untapped hydrocarbon reserves and its legal territorial waters adjacent to North African producers, position the country as more than a transit state—it is a critical enabler of bi-continental connectivity. Safeguarding and capitalizing on these geographic and resource strengths is essential to ensuring Europe’s long-term energy security and advancing Greece’s emergence as a key regional player.

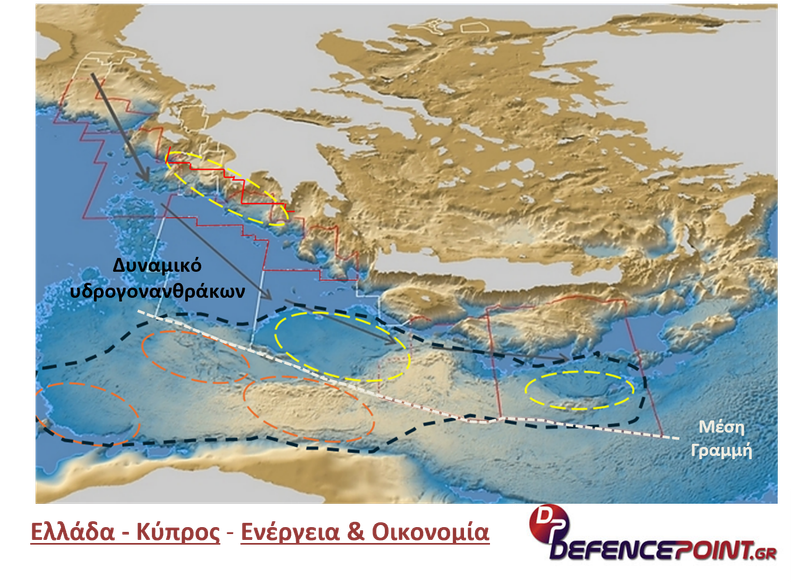

Greece is not just vital to the Eastern Mediterranean puzzle, it’s also critical to the broader North African energy landscape. This is due to potential hydrocarbon reserves off Crete and in the Ionian Sea, located opposite Libya and Algeria. Estimates suggest up to 2,550 Bcm of gas (equivalent to 12–15 billion barrels of oil). Even a 20% commercial yield could significantly improve Greece’s trade balance and allow for gas exports, shifting its role from transit country to producer. Confirmed reserves in the Eastern Med represent just 1.7% of global totals, but if Greece and Libya develop their fields on either side of their maritime border, the region could hold 4–5% of global reserves. This would not only boost production but also strengthen energy connectivity between Europe and North Africa via legal Greek waters.

North Africa is emerging as a dynamic and strategically important hub for energy and technology, competing with the Eurasian corridors IMEC and BRI, thanks to its strong energy potential and expanding transport and communications infrastructure. Despite political instability, North Africa boasts a relatively advanced energy and telecommunications transport network, making it a competitive alternative to emerging Eurasian corridors such as IMEC and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The region already hosts numerous existing and planned oil and gas pipelines, complemented by major telecommunications projects that enhance transport network development. North African oil and gas pipelines are being designed and constructed in parallel with electric and telecom interconnections to Europe. For example, the Medusa Project—an 8,700 km undersea cable supported by the EU—is scheduled to connect Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt in 2026, providing access to 5G internet. Meanwhile, Egypt and Tunisia are expanding regional electricity links to export surplus power, and Morocco is bolstering its grid connections to supply hydrogen to European markets.

Algeria and Libya remain key oil and gas exporters. Algeria, in particular, has increased its pipeline exports to Europe as part of the EU’s strategy to reduce dependence on Russian natural gas. Algeria’s untapped shale gas reserves are estimated at 20 trillion cubic meters (Tcm). Its proven onshore gas reserves are calculated at 4.5 Tcm—about 1.3 times greater than those of the Eastern Mediterranean (Israel, Egypt, Cyprus), and 1.8 times the theoretical reserves of Greece.

Algeria aims to increase its natural gas production to 200 billion cubic meters (Bcm) annually, up from the current 137 Bcm, in order to boost exports to Italy, Spain, and Germany. It also has a liquefaction capacity of 25.3 million tons per year. When compared to the EU’s annual gas needs (370 Bcm), Algeria’s exports could cover 54% of Europe’s demand on a global scale.

Morocco is emerging as a key gas transport hub for West Africa. It is well-suited for importing liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the United States. Additionally, the Nigeria–Morocco Gas Pipeline, stretching 5,600 kilometers, could transform Morocco into a true regional gas hub. Major companies, including ExxonMobil and Chevron, are eyeing these opportunities along Morocco’s Atlantic coast.

Libya holds Africa’s largest proven oil reserves—48.4 billion barrels—as well as 1.5 trillion cubic meters (Tcm) of natural gas. Moreover, gas resources along the median maritime line shared with Greece may offer significant returns in the future.

Egypt, once a rising LNG exporter, is now seeing a sharp decline in gas exports due to falling production and rising domestic demand. The country aims to increase its renewable energy share from 5% in 2024 to 42% by 2030, but its outdated electrical grid poses a major obstacle. High costs and limited financing further slow down the development of large-scale renewable projects.

Three major natural gas pipelines currently link North Africa to Europe: one connects Algeria to Italy via Tunisia and Sicily, another runs from Libya to Italy, and a third links Algeria to Spain through Morocco. Together, these pipelines have a combined delivery capacity of approximately 65 billion cubic meters (Bcm) per year. Looking ahead, two major projects—the Nigeria–Morocco pipeline and the Trans-Saharan pipeline to Algeria—are expected to add another 60 Bcm annually, significantly enhancing West Africa’s export potential. Additionally, a planned hydrogen pipeline could transport 4 million tons of hydrogen per year, equivalent to roughly 11 Bcm of natural gas, further diversifying Europe’s future energy mix.

" Defense Point June 21, 2025" Yannis Bassias

Selected parts translated in English from the original article in Greek

Διασυνδεσιμότητα Ευρώπης-Αφρικής και ο ρόλος της Ελλάδας