The King Natural Gas

The global demand for computing power is growing exponentially, and most of the electricity needed to run AI data centers will still come from natural gas. However, by 2027, the United States is expected to have completed just 4–5 new facilities, leaving a gap of about 8 units. This deficit becomes particularly important as Washington seeks for the next three years to double its LNG exports to Europe, from 60 to 120 billion. cubic meters (bcm) per year.

Current US LNG exports amount to about $14 billion. cubic feet (BCF) per day, with an annual growth rate of 40%, which is about 5 bcf extra each year. Nevertheless, this total volume remains insufficient in relation to the projected needs of the data centers, which are estimated to reach 12 bcf per day if translated into exclusive consumption of natural gas. The emerging energy gap intensifies competition for new natural gas production fields and highlights the strategic importance of LNG infrastructure worldwide as a critical link in the AI chain. The big beneficiaries are not only producers, but also infrastructure managers, those who can move quickly, invest strategically and take advantage of the volatility of geopolitical balances and prices.

The SE Mediterranean: Fields of claim and LNG nodes

The companies are strengthening their presence in the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa, both in the production and sale of LNG to countries in the region. Major LNG exporters such as Exxon and Chevron see Greece as an important transit hub and not just for hydrocarbon exploration. Greece, with the infrastructure in Revithoussa and Alexandroupolis, acquires a strategic role as a hub for regasification and transit. With the ban on the import of Russian natural gas into the EU from 2026, Bulgaria, Serbia and from 2027 North Macedonia will be supplied through Alexandroupolis and the DESFA network. Greece, as a transit operator with increasing transit volumes and a competitive character, plans to reduce transport fees to the Balkans and Ukraine by 10%.

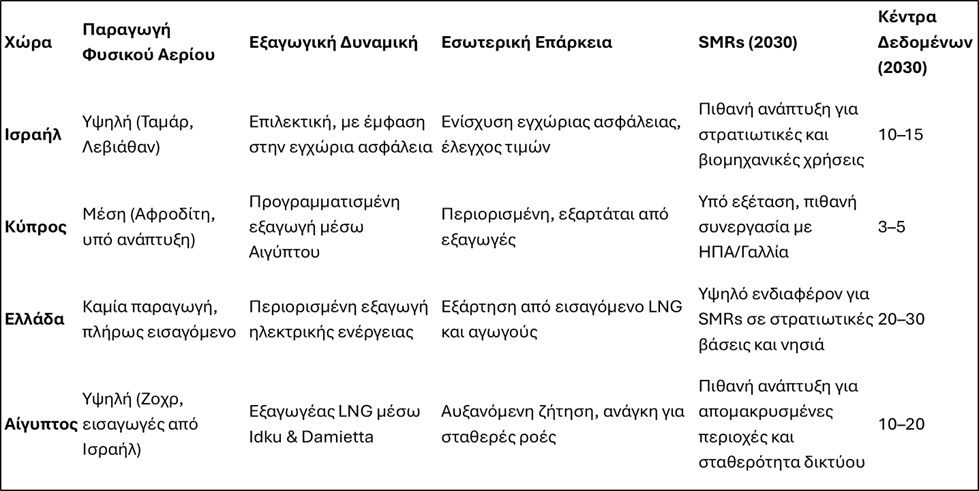

There are also differences such as Turkey's, which, although it looks to Libya, Saudi Arabia and Iraq for oil, has no intention of stopping gas and oil imports from Russia.

Israel, although it already supplies Egypt through the Tamar and Leviathan fields, chooses to delay approval for the expansion of exports from Leviathan. This decision is geopolitical and internally managed. The Israeli government seeks to enhance security of supply for the domestic market, ensure stable prices for consumers, and prepare for increased demand from industry and power generation, especially in conditions of geopolitical instability.

Similarly, Cyprus, which plans to start exports to Egypt from 2027 and strengthen them after 2031, will have to balance between an extrovert strategy and internal sufficiency. The development of the Aphrodite and Saturn fields and their connection to Egyptian LNG infrastructure creates opportunities, but Cyprus should ensure that it maintains sufficient reserves for its own needs, whether for power generation, strategic storage, or future industrial use. In this context, the energy policy of these countries cannot be one-dimensional. Export dynamics are combined with national energy security, flexibility in times of crisis, and protection of the social and economic fabric from external price and supply fluctuations.

Unlike Israel and Cyprus, which have their own natural gas reserves and are called upon to balance between exports and internal sufficiency, Greece does not have its own production. The natural gas it uses is imported or transited, through pipelines and regasification infrastructure, which limits national flexibility in times of crisis or price volatility. Despite its pivotal role as a gateway for natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean and Southeastern Europe, Greece remains among the most expensive countries in the EU in terms of electricity, with an average clearing price of around €130/MWh in early November. Electricity exports remain limited relative to imports, which highlights the country's structural dependence on imported natural gas, not only as a fuel, but also as a balancing mechanism for the system, especially when production from RES is limited. This energy profile makes Greece vulnerable to external price and supply fluctuations, while limiting its ability to act as a stabilizing factor in the region. In order to regain strategic autonomy, the country must claim an active role as a producer of hydrocarbons, structuring its geopolitical influence and strengthening its internal sufficiency in the horizon of 2030.

Γιάννης Μπασιάς: Ο Βασιλιάς Φυσικό Αέριο - KontraNews

"Κυριακάτικη Κόντρα - Έντυπη Εκδοση - Αρθρο - November 9, 2025"

Yannis Bassias – Selected parts translated in English from the original article in Greek